This blog remarked in April on Buffalo’s former Commission on Human Relations, which investigated a Buffalo police officer in 1966 for the fatal shooting of an unarmed Black youth. That body’s present-day successor, the Commission on Citizens' Rights and Community Relations (CCRCR), has the power to issue subpoenas and hold public and private hearings to mediate discrimination disputes, including police misconduct complaints, pursuant to the Charter of the City of Buffalo.

The CCRCR’s bylaws require it to meet quarterly to fulfill the City Charter’s requirement that it meet at least four times a year. The Charter also requires each of the city’s boards and commissions, including the CCRCR, to produce an annual report.

According to public records, the CCRCR has not met since 2020, and its last annual report was for the year of 2019.

In response to a Freedom of Information Law request that I filed in my free time this March, the CCRCR’s executive director, Jason Whitaker, stated that the CCRCR has no records of any subsequent meetings, hearings, or reports, since “at the beginning of the pandemic, an administrative hold was placed on all commission’s activities including the CCRCR.” In response to a second request, Mr. Whitaker and a city attorney replied that there are no records related to the “administrative hold” and that no officer or employee of the CCRCR has a work calendar.

My initial request also sought a reasonably detailed current list by subject matter of all records in the possession of the agency (which each state or local government agency in New York State is required by law to update each year) and a record of the name, public office address, title, and salary of every officer and employee (which state law also requires each agency maintain). Mr. Whitaker declined to provide either of these records but pointed to the CCRCR’s website and to the OpenData Buffalo website, whose payroll records indicate that in 2022, the city paid the CCRCR director $101,071 dollars and the CCRCR secretary $54,724 dollars. Their combined pay since 2020 tops $500,174 dollars, according to the payroll dataset.

Of the budgeted salaries for the 34 directorships in the city’s 2022-2023 adopted budget, the CCRCR director’s $102,683-dollar budgeted salary is higher than half. Of the 16 other secretaries budgeted, the CCCRC secretary has a higher budgeted salary than 13 of them and the same budgeted salary as the Secretary to the Commissioner of Police. Buffalo’s Police Commissioner oversees over one thousand employees, while the CCRCR director oversees just one (the CCRCR secretary).

In the Mayor of Buffalo’s 2023-2024 recommended budget, salaries for the CCRCR director and CCRCR secretary increase to $105,764 and $55,061 dollars. After the inclusion of $700 dollars budgeted for supplies, rentals, printing, and binding (up from $600, despite that the recommended budget shows that the CCRCR has not used any of these funds from the last two budgets), the budget’s recommended allocation for the CCRCR is $166,175 dollars.

This sizeable taxpayer expense appears wholly unjustified in light of the city’s indication that the CCRCR is paralyzed by an undocumented prohibition on the duties it is empowered by law to perform. Even worse, these duties include responding to and resolving complaints of discrimination by our government, which are allegations of serious federal crimes.

Buffalo’s elected officials must take action if they are to honor their oaths of office. The clear long-term solution is to replace unaccountable bureaucratic appointees with a transparent and directly elected citizens review board, for which this blog has previously advocated.

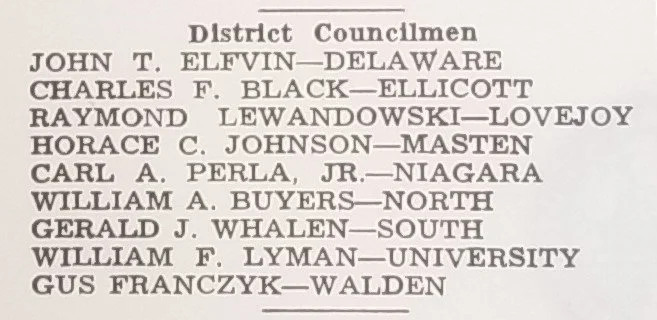

During its budget deliberations this month, the Buffalo Common Council has an opportunity to reallocate the CCRCR’s funding and earmark it for an independent and effectual oversight body. Buffalo residents have opportunities to demand that change when completing the council’s budget survey and when speaking in person or remotely at the council’s public hearing on the budget, which is scheduled for Tuesday, May 16 at 5:00 PM. The social welfare organization Our City Action Buffalo is scheduled to host an online budget information session the night before.